Stepping away from politics, I’d like to put in yet another plug for my favorite non-stallionic site on the web: the genius that is Shatner’s Toupee. Since 2009, their toupological studies department has chronicled the history of the hairpiece of He Who Is Shatner. I have no idea who came up with the idea or who’s writing the thing, but I do know that it’s extraordinarily well-executed, insightful, clever, and filled with tremendous affection for William Shatner. It’s well worth reading, whether or not you have a compelling interest in fake hair.

I give you this background in order to steal a page from their playbook. My favorite posts are the ones they call “Full Toupological Analyses,” where they take one of William Shatner’s many screen appearances and review it at length, concluding with an assessment of how well the Shatner Toupee holds up in the process. I especially recommend their reviews of Incubus, the first full-length feature film spoken entirely in Esperanto:

I give you this background in order to steal a page from their playbook. My favorite posts are the ones they call “Full Toupological Analyses,” where they take one of William Shatner’s many screen appearances and review it at length, concluding with an assessment of how well the Shatner Toupee holds up in the process. I especially recommend their reviews of Incubus, the first full-length feature film spoken entirely in Esperanto:

Roger Corman’s The Intruder, where Shatner brilliantly plays a racist precursor to Glenn Beck:

Roger Corman’s The Intruder, where Shatner brilliantly plays a racist precursor to Glenn Beck:

And, of course, the full toupological analysis of the noble failure that is Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

And, of course, the full toupological analysis of the noble failure that is Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

Quite by accident, I came across a previously unknown – at least to me – magnificent piece of Shatneria, a toupological gem that the good folks at Shatner’s Toupee have yet to analyze. So, at the risk of stealing their shtick, I hereby provide for you a full toupological analysis of a 1974 episode of The Six Million Dollar Man entitled “Burning Bright.”

Quite by accident, I came across a previously unknown – at least to me – magnificent piece of Shatneria, a toupological gem that the good folks at Shatner’s Toupee have yet to analyze. So, at the risk of stealing their shtick, I hereby provide for you a full toupological analysis of a 1974 episode of The Six Million Dollar Man entitled “Burning Bright.”

First, some background.

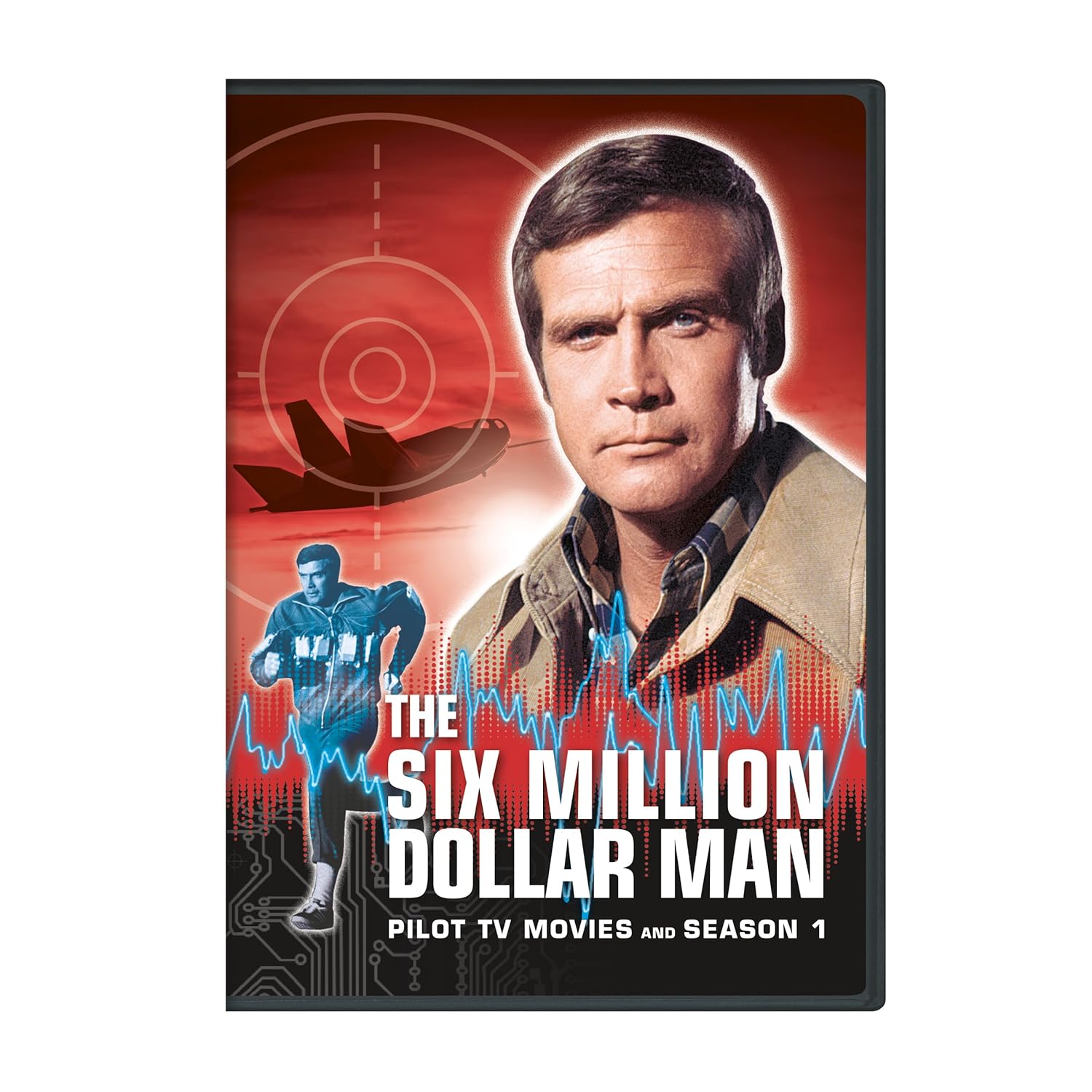

I received the first season of the Six Million Dollar Man on DVD as a Christmas present, and I have since devoured all thirteen episodes and the bonus features to boot. This is really the first television series I remember watching in its original run, beginning at a time when I was only six years old. I have great affection for the show as a whole, even though, on its merits, it really doesn’t deserve it. Nostalgia can cover a multitude of sins, but it can’t turn this show into anything more than a mildly interesting 70s relic.

I received the first season of the Six Million Dollar Man on DVD as a Christmas present, and I have since devoured all thirteen episodes and the bonus features to boot. This is really the first television series I remember watching in its original run, beginning at a time when I was only six years old. I have great affection for the show as a whole, even though, on its merits, it really doesn’t deserve it. Nostalgia can cover a multitude of sins, but it can’t turn this show into anything more than a mildly interesting 70s relic.

My biggest beef with the thing is that every episode attempts to spread about twenty minutes of plot over the course of almost an hour, so the pace of the thing is deathly, deathly slow.

Take the first scene in the pilot film, for instance, where you meet one of the main characters – a guy named Oliver Spencer, the man who makes the decision to spend the six million bucks to rebuild the title character. How do you meet him? Well, you get to watch him walking alongside Federal Building in Westwood, California – it’s supposed to be in Washington D.C. but you can see the Wilshire Boulevard address over the front door. Then, using a cane, the dude walks up to the front door of the building, walks into the building, gets in the elevator, presses the button, and rides the elevator up, waiting twice as the elevator opens to let the rest of the people off on their floors. Then you watch him walk into a conference room full of people, walk to the head of the table, and then unlock a briefcase before he says anything – and the first thing he says is “distribute these, please,” to his secretary as he passes out a bunch of random papers.

The whole sequence takes one minute and forty-eight frickin’ seconds, or, in television terms, an eternity.

Here. Watch it for yourself if you don’t believe me. It’s much, much less exciting than it sounds.

Notice the insertion stock footage of the Federal Building and how it has a different texture from the rest of the sequence. Each episode is crammed with cheap-looking stock footage, and often the same stock footage. Indeed, one identical shot is used at the beginning of two separate episodes. In the first, “Doomsday and Counting,” it’s supposed to be an island off the coast of Russia. In “Last of the Fourth of Julys,” the identical film, complete with annoying lens flares, is used to identify the coast of Norway(!). What makes it especially bizarre is that it’s clearly a shot of the Southern California coastline near Point Mugu, which, correct me if I’m wrong, does not resemble either Russia and Norway, let alone both.

Perhaps Oliver Spencer personally filmed this footage in exile, as he disappears after the pilot movie, where you learn that civilian Steve Austin is drafted against his will to serve the OSO – the Office of Special Operations. When the series begins, Oscar Goldman appears and replaces Spencer – or maybe we’re supposed to pretend Spencer got plastic surgery, a name change, and something to fix his bum leg. The entire name of the agency changes, too – it’s now the OSI – Office of Scientific Intelligence, or some such, and Steve Austin is a Colonel in the Air Force, not a civilian, and he and Oscar are buddy buddy, unlike his strained relationship with the prickly and far more interesting Mr. Spencer, who sends Steve on a suicide mission just to test him and asks if they can keep him drugged and unconscious between assignments.

Continuity really isn’t an issue here, and, indeed, one can watch the episodes entirely out of sequence and not feel confused. Steve is reintroduced each time as an astronaut who walked on the moon, and he always recounts his origin story to some hapless guest star, so you’re always starting fresh and never have to feel like anything that happened before really matters. Plus this bit of incessantly repeated exposition also helps to pad out the running time, which seems to be the producers’ primary goal.

To that end, everything Steve does bionically is shown in slow motion. That means that in the episode “The Day of the Robot,” Lee Majors fights John Saxon for a full eight and a half minutes. Seriously. EIGHT AND A HALF MINUTES. IN… SLOW… MOTION. I could show you the whole thing, but instead, I recommend you just look at this picture –

– and imagine starting at slight variations of this for EIGHT AND A HALF FREAKING MINUTES.

That’s not to say the show is without its charms. Lee Majors is the perfect embodiment of small screen macho – impressive but not intimidating, sort of a Steve McQueen with all the edges smoothed away. It’s delightful to see the ridiculously advanced things they do with computers that still read punchcards, and it’s even more fun to see the shows chock full of 1970s guest stars who apparently alternate between appearances on Match Game PM and the Six Million Dollar Man.

Which brings us, of course, to the good Mr. Shatner and his portrayal of Josh Lang, a disturbed astronaut who stands at the center of the tenth episode of the first season, “Burning Bright.”

______________________

I was astonished when I saw the beginning of this episode, as it opens with perhaps the most delightfully bizarre Shatner monologue ever recorded. The visuals are typical Six Million Dollar dreck, as it shows mostly NASA stock footage of a space walk interspersed with shots of Shatner in a cheap spacesuit filmed in front of a cardboard cutout of the moon. But the text! The delivery! It’s pure Shatnerian weirdness delivered in a camp, over-the-top style that, by the end, makes every histrionic Captain Kirk speech look tame by comparison. I still can’t decide if it’s unspeakably awful or one of the very best things the man has ever done.

Behold, and marvel!

So what to make of that? And who is the guy “Andy” that Josh Lang was talking about? The folks at NASA are baffled, and they call in Josh Lang’s good buddy Steve Austin to help. They tell Steve that Lang’s brain is now “supercharged” by some kind of electrical field he encountered on the spacewalk, and his erratic behavior will make it impossible to send him up on the next “space shot.” Steve asks his superiors to let him talk to Josh and see if he can’t straighten things out.

Steve then undergoes “testing” of his bionics, which provides an opportunity to recycle about three minutes of old footage from previous episodes, including two shots we just saw in the opening credits. (Apparently, his bionic tests require him to change outfits with each different exercise.) At the end of the test, he gets a phone call from Josh, who asks to meet him at Ocean World Amusement Park, a place where Josh feels “comfortable.” It’s there that the two astronauts finally meet face-to-face, in front of an aquarium where we half-expect to see Leonard Nimoy swimming a la Star Trek IV.

Steve then undergoes “testing” of his bionics, which provides an opportunity to recycle about three minutes of old footage from previous episodes, including two shots we just saw in the opening credits. (Apparently, his bionic tests require him to change outfits with each different exercise.) At the end of the test, he gets a phone call from Josh, who asks to meet him at Ocean World Amusement Park, a place where Josh feels “comfortable.” It’s there that the two astronauts finally meet face-to-face, in front of an aquarium where we half-expect to see Leonard Nimoy swimming a la Star Trek IV.

Josh tells Steve that he knows he’s saying things that are “way out there,” but he can’t turn off the flood of new ideas pouring into his brain since his encounter with the electrical field. Steve reports the exchange to NASA, and they decide to ground Josh and keep him under observation. While Steve is defending Josh and asking for more time, the phone rings to report that Josh is tearing up reams of paper in the computer room and claiming to have found a mistake in the program for the next space shot. Everyone thinks he’s crazy except Steve.

Josh tells Steve that he knows he’s saying things that are “way out there,” but he can’t turn off the flood of new ideas pouring into his brain since his encounter with the electrical field. Steve reports the exchange to NASA, and they decide to ground Josh and keep him under observation. While Steve is defending Josh and asking for more time, the phone rings to report that Josh is tearing up reams of paper in the computer room and claiming to have found a mistake in the program for the next space shot. Everyone thinks he’s crazy except Steve.

Steve then asks Oscar Goldman to check on the computer error, and, at the same time, also run a computer query to determine whether or not Josh Lang was right when he said that the sun is the origin of the universe. (Seriously. I’m not making that up. The show posits that somehow, a 1970s computer with magnetic tape and punch cards would be able to determine, magically, whether or not the sun is the origin of the universe. Remember, these computers have about 1/1000th the computing capacity of my iPhone.)

Steve and Josh then go jogging in hideously ugly 1970s jumpsuits which show off Steve’s hairy chest and Josh’s unsettling affinity for baby blue:

While jogging, Josh stops at a group of high voltage electrical poles and decides to climb them, all the while talking to the mysterious “Andy” that he had mentioned in space. “Hang on, Andy!” he calls. “I’m coming!”

While jogging, Josh stops at a group of high voltage electrical poles and decides to climb them, all the while talking to the mysterious “Andy” that he had mentioned in space. “Hang on, Andy!” he calls. “I’m coming!”

He ends up grabbing a power line and electrocuting himself. Steve jumps up to rescue him. Josh intuits immediately that Steve is bionic. “How’d you know?” Steve asks. Because the “name [bionics] just popped into my head,” Josh answers. Josh tells Steve that with his bionics and with Josh’s “far out brain,” they now constitute “superior types,” a whole new species. But when asked about who Andy is, Josh angrily denies that he knows anyone named Andy. So Steve tells Josh that he truly is too unstable to go back to space, and Josh reluctantly agrees.

He ends up grabbing a power line and electrocuting himself. Steve jumps up to rescue him. Josh intuits immediately that Steve is bionic. “How’d you know?” Steve asks. Because the “name [bionics] just popped into my head,” Josh answers. Josh tells Steve that with his bionics and with Josh’s “far out brain,” they now constitute “superior types,” a whole new species. But when asked about who Andy is, Josh angrily denies that he knows anyone named Andy. So Steve tells Josh that he truly is too unstable to go back to space, and Josh reluctantly agrees.

The next day, Steve rifles through Josh’s personal records and discovers a $100,000 life insurance policy on Josh payable to someone named Ernesto Arruza in Texas. In the meantime, Josh is locked up in a hospital and placed under observation, but he escapes by mentally overpowering his guard, knocking him unconscious, stealing his uniform, and walking out the door when the next shift arrives.

NASA discovers Josh’s escape as Steve gets a note from Josh asking him to meet him at the waterpark, alone. Once there, Josh tells Steve he can now talk to dolphins. Dolphins hold the key to the mysteries of the universe, doncha know. Josh want to talk the dolphins with him into space and bring them to the electrical field that supercharged his brain. He explains this in a deliciously goofy speech that has all the trademark elements of Shatner’s hammiest work.

NASA discovers Josh’s escape as Steve gets a note from Josh asking him to meet him at the waterpark, alone. Once there, Josh tells Steve he can now talk to dolphins. Dolphins hold the key to the mysteries of the universe, doncha know. Josh want to talk the dolphins with him into space and bring them to the electrical field that supercharged his brain. He explains this in a deliciously goofy speech that has all the trademark elements of Shatner’s hammiest work.

The plot then kicks into overdrive, both in terms of pace and silliness. Oscar comes back and claims that a computer less powerful than a Pong terminal confirms that, yes, the sun is the center of the universe, so Josh convinces Steve that the next space shot should include a dolphin(!). NASA, however, just doesn’t seem to be interested in extraterrestrial aquatics. They decide Josh needs to be locked up for good, but Josh again overpowers his captors with his brains and then heads out to Texas and Ernesto Arruza, who Steve discovers is the father of Josh’s childhood friend Andy, who died when they were climbing electrical wires. Josh is becoming increasingly erratic as he loses control of his mind, even killing a sheriff’s deputy by accident. This leads to a final confrontation with Steve on another set of power lines, another melodramatically absurd, over-the-top Shatner rant filled with mathematical gibberish, and, alas, a tragic ending that ensures that there will be no “Burning Bright II.”

Evidence suggests that Bill Shatner does not have high regard for this bit of work during what has come to be known as his “lost years.” In his book Star Trek Movie Memories, he recalls:

Over the course of the next several years I accepted all offers, and was lucky enough to keep busy as an actor. Some of the roles, a guest villain shot on Columbo and featured spots on shows such as The Name of the Game and Mission Impossible, were quite good. Others, like hawking Promise margarine all over television, or battling The Six Million Dollar Man, were equally bad. A few, in films such as Big Bad Mama and The Devil’s Rain, can best be described as just plain ugly.

– Star Trek Movie Memories, page 18

So Shatner thinks “Burning Bright” isn’t ugly, just bad. He’s right – all things considered, it is pretty bad. At the same time, I think he’s overlooking much in this episode that is praiseworthy, all of which stems from his own committed performance.

I recognize that the story of an astronaut who gives his life in an attempt to launch dolphins into space while talking to dead childhood friends is not one that has been told in many media, and I think there’s a reason why. And that reason is that it’s stupid. It’s really stupid.

But dag nab it if Bill Shatner doesn’t recite algebraic fiddle faddle as if he’s giving Marc Antony’s funeral speech for Caesar.

One of the reasons Shatner has become – and remained – a beloved icon is his willingness to throw himself with reckless abandon into whatever role comes his way, even one as laughable as this. Most actors would shy away from the risk of appearing ludicrous, but Shatner has no such inhibitions. One watches in horror, then fascination, then admiration as he howls about the sun as the center of the universe, x1=A2 omega cosine T.

Who else would want to do this? Who else could do this even if they tried?

Imagine, for instance, a parallel universe where Shatner had landed the role of Steve Austin after finishing his run on Star Trek, and therefore Lee Majors is the one cast as the erratic, dolphin-chummy astronaut. Imagine Majors calling out to Andy and climbing the power line and howling about interstellar geometry until his brain fried. Yeah, good luck with that.

This show was filmed only five years after Star Trek went off the air, and, by this time, the reruns of the show were gathering steam and driving Star Trek deep into the national psyche. It seems clear that Shatner’s casting was designed to capitalize on the popularity of the Kirk persona, reimagining the good starship captain as a deranged NASA astronaut. But what’s even more interesting is how prescient the whole thing seems to be when viewed almost forty years after the fact.

Harve Bennett, the show’s producer, went on to save the Star Trek franchise eight years later as the producer of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, unarguably the best piece of Trek ever committed to film. (Don’t argue with me on that one. I said it was unarguable.) The idea of launching dolphins into space seems like a stunted prequel to Star Trek IV, when terrestrial mammals – albeit whales, not dolphins – finally do make it to the final frontier with Shatner’s help. And Josh Lang’s bizarre Minnesota Flats impression would have made a great back cover to Shatner’s current musical disaster, Seeking Major Tom.

Let’s move swiftly to the hair. (I’ve always wanted to write that.)

Longtime readers at Shatner’s Toupee will recall the four distinct phases of Shatner’s toupological history: the Jim Kirk lace, the Lost Years, the TJ Curly, and the Denny Katz. (I won’t define them here for you; you can read all about them over at ST, and this post is already far too long.) This appearance is smack dab in the middle of the Lost Years period, when Bill was likely too poor to afford a decent rug and too far off of Hollywood’s radar screen to merit a studio springing for a piece worthy of his talents. The result is what may very well be the absolute nadir of the Lost Years period and the use of perhaps the ugliest toupee Bill Shatner has ever worn.

I know, I know. Them’s fighting words. But how on earth could someone appear on national television looking like this?

Much of the episode takes place outdoors, so this sloppy, unkempt toup, which looks more like painted straw than actual hair, is repeatedly exposed to direct sunlight and shown in extreme close-up, silencing all doubters who might think this greasy black bird’s nest could have possibly grown from a human scalp. Behold this:

Much of the episode takes place outdoors, so this sloppy, unkempt toup, which looks more like painted straw than actual hair, is repeatedly exposed to direct sunlight and shown in extreme close-up, silencing all doubters who might think this greasy black bird’s nest could have possibly grown from a human scalp. Behold this:

Notice in all the shots the distinct contrast between the artificial helmet of black broom fibers and the small thatch of real hair at the sideburns.

Notice in all the shots the distinct contrast between the artificial helmet of black broom fibers and the small thatch of real hair at the sideburns.

Other than the truly wretched nature of the toup, there seem to be no remarkable toupological moments to speak of, where Shatner interacts with the toup in ways that are revealing or interesting. Indeed, the producers seem eager to conceal the toup as often as possible, either with a space helmet or an MP’s cap, as pictured earlier.

Other than the truly wretched nature of the toup, there seem to be no remarkable toupological moments to speak of, where Shatner interacts with the toup in ways that are revealing or interesting. Indeed, the producers seem eager to conceal the toup as often as possible, either with a space helmet or an MP’s cap, as pictured earlier.

There is, however, one exception.

In the clip posted above, when Steve is climbing up the electrical pole to rescue his buddy, Josh uses the power of his mind to cause Steve excruciating pain, whereby he grabs the side of his head in agony, like so:

He then grabs his head with both his hands, as indicated by the following picture:

He then grabs his head with both his hands, as indicated by the following picture:

It’s not as visible in the tighter shot, but it’s clear in both cases that Lee Majors has no qualms about his hands making contact with his hair. However, when William Shatner is experiencing similar cranial anguish, his hands reach toward his face and curl his fingers into semi-fists, only to brush against his face rather than touch his fake hair.

It’s not as visible in the tighter shot, but it’s clear in both cases that Lee Majors has no qualms about his hands making contact with his hair. However, when William Shatner is experiencing similar cranial anguish, his hands reach toward his face and curl his fingers into semi-fists, only to brush against his face rather than touch his fake hair.

It looks something like this.

So what we have here, my fellow distinguished students of toupology, is a classic example of Fake Hair Brain Pain, which ought to go alongside the Real Hair Reflex as a notable, previously undiscovered toupological phenomenon.

And thus concludes our toupological adventure. It was lengthy, silly, and somewhat pointless, but I had an awful lot of fun putting it together, and now that you’ve read it, you can’t unread it.

You may applaud.